Dear Friends, Family, Neighbors, and Those of You I Don’t Yet Know —

Like many people, I’ve been following events in Ukraine and Russia for the past few weeks. First and foremost, the scenes of war have made me grateful for the safe and peaceful life I lead — for the ability to run to the grocery store and find the aisles crowded with delicious, fresh food; to get clean, drinkable water from my kitchen tap; to lie down in my own bed at night; to feel safe.

I share and understand the President’s hesitancy to engage in direct combat with Russia. Maybe it’s because I remember the Cold War — a long period of time during my childhood when I never felt safe, not even in my own bed at night. At any moment, the sky could fill with nuclear missiles, enough to destroy the world many times over. The nuclear arsenals still exist. There are still enough bombs to destroy the world again and again. But many of us seem to have forgotten this sad fact, or are too young to remember it. We worry about climate change, but in fact, the other existential threat is more likely to end the world in our lifetimes.

For a couple of years in the 1980’s, my husband taught at Princeton University. While we were there, I got to know the philosopher David Lewis. It’s been said that Lewis was one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century. It meant more to me that he was a delightful and eccentric man. I’m not a philosopher myself, so most of my conversations with him were limited to the two joys we had in common — trains and science fiction. But a couple of his philosophical theories fascinated me so much that I waded through some of his papers on the subjects. One was his theory of modal realism, which led him to a belief that many possible versions of the world could exist at once. One of my first published stories, “Clotaire’s Balloon,” came directly out of Lewis’s ideas about possible worlds and counterparts.

But another of Lewis’s ideas gripped me just as ferociously. In an obscure paper co-authored with another academic whose name I no longer remember, Lewis discussed a strange notion about mutual assured destruction. “Mutual assured destruction” is one of those phrases from the past that we would call a meme today. In the 1970’s and 80’s it was everywhere. That is, the horrifying fact that both Russia and the U.S. had roughly equal ability to destroy each other (and most of life on Earth, collateral damage), both sides were aware of it, and this awareness is all that kept both sides from starting a war. Any war would most assuredly result in mutual destruction. No one would win. In every practical sense, both sides would lose. But Lewis added a new and grisly observation. Mutual assured destruction (MAD, for short; few acronyms have ever been so appropriate) only worked when both sides fully and truly intended to respond in kind if the trigger was pulled. The instant one side doubted the sincerity and intentions of the other, MAD ceased to be a deterrent.

When I look at the news and videos coming out of Ukraine tonight, it makes my heart ache. I want to do something about it. As we know, a bully who is hurting people has to be stopped. Unfortunately, the world of geopolitics is no less crazy today than it was 50 years ago. Thousands of American nuclear arms are aimed at thousands of Russian nuclear arms and vice versa, ready to be let loose on a moment’s notice by people with itchy fingers. Mutual Assured Destruction is still in place. No one wants an all-out nuclear war, but if the right triggers are pulled, no one will be able to prevent one. The trigger could be something as small as a squadron of American fighter jets veering into Russian territory…

Sorry…that was an unusually bleak and rambling beginning. But we have now arrived at the real subject of tonight’s Odd Company: cancel culture. This will no doubt seem to come out of the blue, but there is a connection, I promise. In an effort to put pressure on Putin while staying far away from the MAD triggers, the West is using economic and cultural sanctions. There is a certain similarity between sanctions and cancel culture. Yup. Some people feel Russia’s being cancelled. I read an article about that claim in a recent issue of The Atlantic.1 And it got me thinking. Always dangerous.

When we say someone’s been “cancelled,” we usually mean they’ve deliberately been made into a social outcast. For someone to be truly cancelled, the populace as a whole must participate in the public shaming of the cancelled individual. The cancelled person becomes so isolated that they can no longer make a living, no longer be part of normal social interactions. No one wants anything to do with them, and even those who may be sympathetic are afraid to help the cancelled person for fear of becoming cancelled themselves.

It’s not a new idea. Consider The Scarlet Letter. And consider that even the ancient Greeks engaged in shunning. In some societies, this type of ostracism is a punishment reserved for only the most serious crimes. After two years of pandemic lock-downs and strife over masks and vaccinations, we’ve all had a taste of how dreadful social isolation can be.

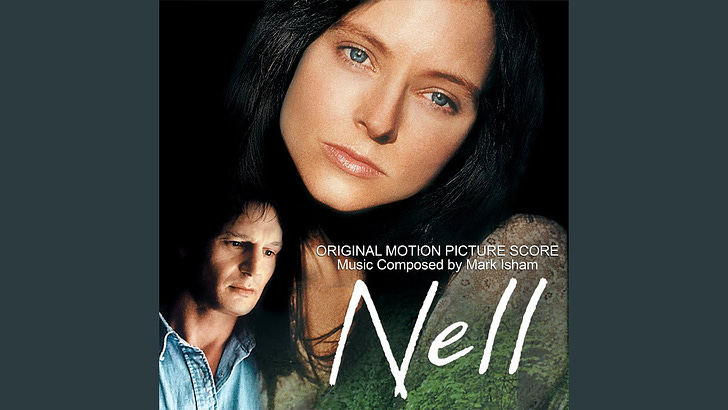

While we all take a minute to contemplate social isolation and the similarities between cancellation and sanctions, here’s a piece of music from the 1994 movie “Nell,” soundtrack by Mark Isham. If you haven’t seen the movie, it’s well worth a look. It’s the story of a young deaf woman who grows up alone and very isolated in the backwoods of North Carolina. Here’s “Don’t Weep for Nell.”

Is Vladimir Putin being “cancelled”? Maybe; maybe not. Certainly the world is punishing him (and his countrymen) for his terrible transgressions, and the tools are economic and cultural isolation — known as sanctions when applied to whole nations. Sanctions are being used because more traditional weapons would bring us too close to mutual destruction. Certainly there are some silly cases. Should we be “banning Russian-bred cats from competitions, and abandoning performances of the Bolshoi Theater shows,” as The Atlantic points out? Probably not. That’s where carefully crafted sanctions begin to bleed into something much less dignified and deliberate.

As so often happens, I feel overwhelmed when I try to consider such things on a global scale. I don’t know what’s the best thing to do in Ukraine. I may never know. The best I can do is to ask myself a smaller, more concrete question. Would I ever join in someone’s cancellation? Would it ever feel right to me?

In civilized places where justice and the rule of law are part of our social contract, punishment for crimes is meted out carefully by people we’ve entrusted with that job. Those accused of crimes are dealt with by prosecutors, by judges, by juries, and an elaborate penal system. When a transgression is dealt with by an off-hand group of ordinary citizens, it’s called vigilantism. The trouble with vigilantism is that there is no judge or trial involved. People go straight from perceived crime to punishment, and the punishment is often a horrific crime in itself, caused by emotions gone wild. Cancellation is a form of vigilantism, and vigilantism is another word for mob rule.

It may be tempting to participate in the cancellation of a person or even the cancellation of a whole group when we feel very strongly about the perceived transgression. Whenever we feel the urge to participate in a mob’s version of justice we should stop and take a few deep breaths. In the space of those deep breaths, we must try to regain a little humility. We might not have all the facts. We might be wrong. And if it’s a real crime, and not just something that personally offends us, there is an entire social apparatus set up to deal with it in as fair and reasonable a way as we can manage.

Till next time…spring, the season of hope, is almost here!

“Of Course Putin Is Being Canceled,” by Helen Lewis, The Atlantic, March 8, 2022.

Thank you for the calming perspective, deep breath, and reminders of the past and blanket reactions. The music was lovely as well, and yes, spring is coming with the honking geese flying by awakening me this morning.